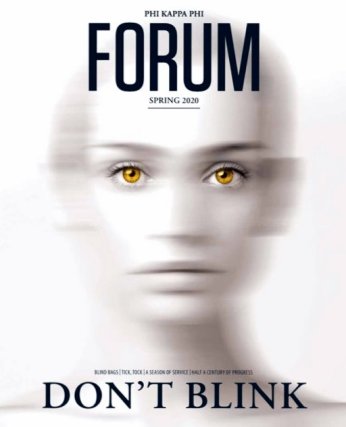

My poem “The Choice” has been published in the spring 2020 issue of Phi Kappa Phi Forum, an honor society magazine. Here are the poem’s first two stanzas:

“The Choice”

I would not wish you to pass.

I would press my hand into your palm

and hope my distress stirs you to choose.

Override the machines. Grab on or let go.

I would press my hand into your palm

and pray for a reflex, anything.

Override the ventilator. Grab on or let go.

Breathe or stop on your own.

The year after my father collapsed with respiratory failure I spent a lot of time, usually alone, in waiting rooms—surgery, ICU, radiology, and more. So many waiting rooms in three hospitals and five care facilities in two states.

The high stakes, the uncertainties, the complications made fiction reading (my usual pastime) difficult. I turned to reading and writing poetry. One of the books I read was Edward Hirsch’s Poet’s Choice, which introduced me to Indian poet Reetika Vazirani and her work.

Vazirani’s three-line poem “Lullaby” stuck with me. And I found myself using Vazirani’s poem as a model. I wrote of my father’s situation over and over, never finding the right words until I learned a poetry form called the pantoum.

The repetition and circling back of the pantoum’s form helped me synthesize the prayer poems I had drafted during my father’s eleven ventilator-dependent months. These months included three times when doctors recommended extubation—twice while my father was unconscious and once while he was awake and clearly not ready to die.

“The Choice,” in the form of a pantoum, helped me to work through this ultimate decision.

Writing exercise

I’ve been curious as to whether the writing process I used might work again with different subject matter (for example, the social isolation of sheltering in place).

- Write about your own subject/topic using Reetika Vazirani’s poem as a model for phrasing, line breaks, and so on. Keep writing and writing until you have multiple versions and approaches and angles and voices. Here’s Vazirani’s poem:

“Lullaby”

I would not sing you to sleep.

I would press my lips to your ear

and hope the terror in my heart stirs you.

—by Reetika Vazirani (1962–2003)

- From among your drafts, highlight the line or lines that “say it best.” Consider which one might work as the first line of your pantoum. Note: This will also become the last line of your pantoum.

- Continue working with material from your drafts within the pantoum structure. One interesting aspect of using this structure is that as you write a stanza, you are also writing two of the lines for your next stanza.

Here’s the pantoum structure of four-line stanzas, notice the repeats:

A

B

C

DB (a repeat)

E

D (a repeat)

FE (a repeat)

G

F (a repeat)

HG (a repeat)

I

H (a repeat)

A (line 1 repeats)

Pantoums aren’t limited to four stanzas, as my outline shows. They can be any length.

Note: When I worked through this process, I titled my “Lullaby”-based drafts. Some of the drafts were “Prayer,” “Meditation,” “Hope,” “Will,” and “No Words.” Ultimately, these titles helped me organize the different approaches and points of view. I encourage you to title your “Lullaby”-based drafts.

- Then, edit, review/peer review, revise, and repeat.

When you need more information or inspiration, it helps to search for and read pantoums on the Academy of American Poets website poets.org or on the Poetry Foundation website poetryfoundation.org. You’ll notice how some poets make slight adjustments in the repeats, while others are to-the-letter faithful in their repetitions.

If you try this writing exercise, I’d be interested to hear about what does or doesn’t work, including your resulting work. If you feel comfortable, please post a comment.